|

ONE GOAL OF THIS BOOK was to put today's debate into perspective. Scapegoating foreigners for domestic problems real or imagined is something of an American tradition. Any student of history knows that the complaints and criticisms lodged against today's Latinos were thrown at previous immigrant groups. But how easily some of us forget.

Ireland was the source country of the first mass migration to the U.S. The Irish flooded America in the middle of the 19 th century, particularly the cities. In 1850, more than a quarter of New York City's residents were born in Ireland. Throughout the 1800s, the U.S. absorbed Irish newcomers at more than double the rate of current Mexican immigration.

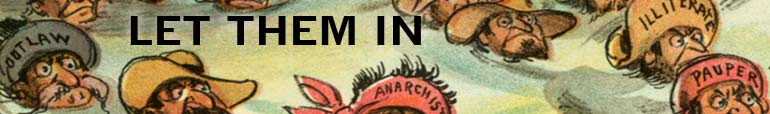

These Irish immigrants were dirt poor peasants back home, but in America they settled in urban ghettos amongst their own kind, where crime and violence and disease were not uncommon. Most were uneducated. Many spoke no English. They worked as domestic servants, ditch diggers, stevedores and in other low-skill, labor intensive jobs that the natives shunned. They were stereotyped as slow-witted drunks and ne'er-do-wells who would never acculturate to America. They were considered members of an inferior race. Political cartoonists drew them with distinctly simian features. Restrictionists of the period called for rounding them up and shipping back to their homeland before they destroyed our culture and social mores with their backward ways.

Of course, the naysayers were wrong. The Irish did assimilate. And then some. They produced writers, painters and presidents. They produced doctors and lawyers and school teachers. They produced civic leaders and businessmen, including Henry Ford, whose father fled the Irish potato famine and who would go on to revolutionize transportation in America.

According to the latest Census figures, as of 2006, 31% of Irish Americans had at least a bachelor's degree, versus 27% of the nation as a whole. And the median annual income for households headed by an Irish American was $54,000, versus $48,000 for all households. Apparently, the children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren of all those hard-working Irish immigrant turned out okay. And although the Irish experience has been replicated by other large immigrant groups from Europe and Asia, this history is often ignored or played down when we discuss Latino immigration today. The opposite should be the case.

People often say that they support legal immigration and oppose illegal immigration. But saying that you oppose unlawful behavior isn't really saying much. All reasonable people oppose illegal behavior in principle. The issue with respect to immigration is whether our current laws make sense, whether they're accomplishing the intended goals of the policy makers who put them in place. Bad laws need to be reformed, not enforced, and current immigration law has left us with upwards of 12 million illegal immigrants in the U.S. Is two-tier fencing, a militarized border and stricter internal enforcement of current law feasible, politically or otherwise? Would it make us safer? What would it do to our traditions? What would it do to our economy? How would it impact the cost of food, housing and countless other goods and services? Would it put U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage in the global marketplace? Would it result in more off-shoring and outsourcing of jobs?

Although it will surely be characterized as such, this book is not an argument for erasing America's borders or dissolving our nation-state. Nor do I pretend that immigration has no economic costs. It does have costs, particularly in border regions and states with generous public benefits. But when those costs are properly weighed against the gains, open immigration and liberal trade policies still make more sense than protectionism, from both a security and an economic standpoint. The U.S. needs to better regulate cross-border labor flows, not end them. We still have much more to gain than lose from people who come here to seek a better life. |

|

|

|