The telephone rang like an alarm, waking Jackie Robinson from deep sleep. “Hello,” he mumbled. It was early morning in Manhattan. Robinson was alone in room 1169 of the McAlpin Hotel, across the street from Macy's. He had been on edge all week, his stomach in knots. As he listened to the voice on the other end of the phone, he was poised to embark on a journey—one that would test his courage, shake the game of baseball to its roots, and forever change the face of the nation. Throughout history, heroic quests have often been launched on grand orders. “The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River…,” wrote Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis. “The free men of the world are marching together to Victory!” General Dwight David Eisenhower exhorted his troops before the D-Day invasion. But the commanding words that sent Robinson on his way this cool, gray morning were uttered by a humble secretary. Come to Brooklyn, she said. He showered and shaved and hurried out of the hotel. He was on his way to meet Branch Rickey, president and part owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and to learn whether Rickey was ready to end the segregation of the races in big-league baseball. In 1947, some southern states still denied the vote to black Americans. Black children were not entitled to attend the same schools as white children. Lynch mobs executed their own bloodthirsty style of justice while local law enforcement officials looked the other way. “I'm sorry, but they done got him,” one sheriff in North Carolina announced that year after a gang of white men made off with one of his prisoners. Black Americans were excluded not only from certain schools but also from parks, beaches, playgrounds, department stores, night clubs, swimming pools, roller-skating rinks, theaters, rest rooms, barber shops, railroad cars, bus seats, military units, libraries, factory floors, and hospitals. In the North, WHITES ONLY signs were far less evident than in the South, but the veiled message was often the same. Black men on business in Chicago, Detroit, or Cleveland usually stayed in black-owned hotels, rode in black-owned taxis, and dined in black-owned restaurants. If a white man became acquainted with a black man, odds were good that the acquaintance stemmed from some service the black man performed for the white man—shining his shoes, for example, or mowing his lawn, or mixing his cocktails. Segregation suffused the nation's culture, and yet profound changes were rippling across the country. Black workers moved from south to north in great waves, reshaping urban spaces and lending new muscle to organized labor. Black soldiers coming home from the war declared they would no longer tolerate second-class citizenship. Federal judges commanded Southern states to stop obstructing the black vote. President Truman signed an order to end segregation in the military. And in major-league baseball, where there were sixteen teams and every player on every one of those teams was white, a single black man was presented an opportunity to change the equation: to make it one black man and 399 white. The test case represented by Jackie Robinson was one of towering importance to the country. Here was a chance for one person to prove the bigots and white supremacists wrong, and to say to the nation's fourteen million black Americans that the time had come for them to compete as equals. But it would happen only if a long list of “ifs” worked out just so: if the Brooklyn Dodgers gave Robinson the opportunity to play; if he played well; if he won the acceptance of teammates and fans; if no race riots erupted; if no one put a bullet through his head. The “ifs” alone were enough to agitate a man's stomach. Then came the matter of Robinson himself. He perceived racism in every glare, every murmur, every third strike called against him. He was not the most talented black ballplayer in the country. He had a weak throwing arm and a creaky ankle. He had only one year of experience in the minor leagues, and, at twenty-eight, he was a little bit old for a first-year player. But he loved a fight. His greatest talents were tenacity and a knack for getting under an opponent's skin. He would slash a line drive to left field, run pigeon-toed down the line, and take a big turn at first base before slamming on the brakes and skittering back to the bag. Then, as the pitcher prepared to go to work on the next batter, Robinson would take his lead from first base, bouncing on tiptoes like a dropped rubber ball, bouncing, bouncing, bouncing, taunting the pitcher, and daring everyone in the park to guess when he would take off running again. While other men made it a point to avoid danger on the base paths, Robinson put himself in harm's way every chance he got. His speed and guile broke down the game's natural order and it left opponents cursing and hurling their gloves. When chaos erupted, that's when he knew he was at his best. On that April 10 th morning, as he rode the subway from Manhattan to Brooklyn, Robinson understood what he was getting into. One prominent black journalist had written that the ballplayer had more power than Congress to help break the chains that bound the descendants of slavery to lives lived in inequity and despair. Before he'd even swung a bat in the big leagues, Robinson was being compared to Frederick Douglass, George Washington Carver, and Joe Louis. The time had come, some writers said, for black Americans to stake their claim to the justice and equal rights they so richly deserved, and now a baseball player had arrived to show them the way. Robinson absorbed the newspaper articles. He felt the weight on his shoulders and decided there was nothing to do but carry it as fast and as far as he could. A cold wind met him as he climbed out of the subway onto the busy streets of Brooklyn. He walked to 215 Montague Street. Waiting for him there was Branch Rickey, a potato-shaped man in a wrinkled suit. Rickey's office was dark and cluttered. He got straight to business, offering Robinson a standard contract for five thousand dollars, the league's minimum annual salary. “Simple, wasn't it?” Robinson recalled later. “It could have happened to you. The telephone rings. You answer it…and you're in the Big Leagues…. Just like a fairy tale…. I went to bed one night wearing pajamas and woke up wearing a Brooklyn Dodgers' uniform.” He knew it was no fairy tale, of course. He knew that a happy ending was far from assured. Most big-leaguers in 1947 had never been on the same field as a black man, had never shared a locker room, a shower, a taxi, a train car, or a table with one. Big-league culture was so thoroughly dominated by white southerners that even rough Italian kids from northern cities experienced shock and isolation upon arrival. There was no telling how Robinson would be received. He was not yet a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and already half a dozen or more of his prospective teammates promised they would quit or demand a trade before they would play with him. Elsewhere, players spoke of a league-wide strike. They were willing to destroy their game rather than see it stained by integration. Others said it would be simpler to take Robinson out with a well-aimed fastball to the head, or with a set of metal cleats driven through his Achilles tendon on a close play at first base, something that would look like an accident. Rickey made only one demand of Robinson. He asked the ballplayer to promise that he would never respond to the racist attacks that would surely come his way. When Rickey quoted a passage from Giovanni Papini's Life of Christ — “But whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also”—Robinson sought clarification. Did Rickey want a player who didn't have the guts to fight back? No, the boss answered, “I want a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.” Rickey walked away while Robinson thought about it for a moment. Though the request would require Robinson to subdue his most basic instincts, and though he had no idea, honestly, whether he could compete without an outlet for his seething sense of indignation, he said he would try. With that, the season's storyline was set. Robinson became baseball's biggest attraction in 1947. According to one survey, he was the second-most famous man in America, trailing only Bing Crosby. Americans yearned for a sense of normalcy in the aftermath of the war, yet everything around them was in flux. Robinson, a human whirlwind, captured the spirit of the time better than anyone. When the Dodgers went on the road, thousands of black men and women traveled great distances to get a glimpse of him, as if to see for themselves that he was real, to share his dignity and glory, to watch this proud, defiant man, the grandson of slaves, stake a claim on their behalf to what Langston Hughes called “the dream deferred.” Railroad companies scheduled special runs. Black parents named their children, boys and girls, after him. White kids from small towns in the Midwest sat surrounded by black men and women at the ballpark and wondered why their parents seemed so anxious. Jewish families in Brooklyn gathered around their dining-room tables for Passover Seders and discussed what Moses had in common with a fleet-footed, right-hand-hitting infielder with the number 42 on his back. White business owners integrated their factory floors and wrote to Robinson to thank him for opening their eyes. Young ballplayers of every color imitated his style, wiping their hands on their trousers between pitches, swinging with arms outstretched, and running helter-skelter around makeshift bases. Jackie Robinson showed that talent mattered more than skin color, supplying a blueprint for the integration of a nation. He led the Dodgers to the greatest season the team's fans had yet seen, to a World Series showdown with the New York Yankees, the outcome in doubt until the final inning of the seventh and final game. But it was something else, something more personal, that captured the American imagination that summer. It was the story of a man filled with fear and fury. It was Jackie Robinson, all alone, taking his lead from the base, bouncing, bouncing, bouncing…and a nation waiting to see what he would do next. |

||

|

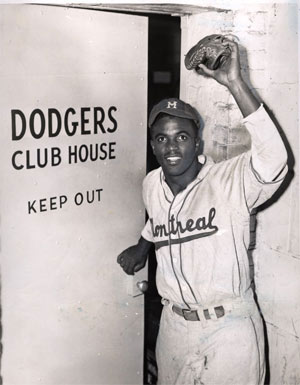

On April 10, after he signed a contract to become a member of the Dodgers, Robinson played one more game with the minor-league Montreal Royals. Here, after the game, he posed for photographers as if entering the Dodger clubhouse for the first time. He was still five days away from his big-league debut, but by now the season's storyline was set. (National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY)

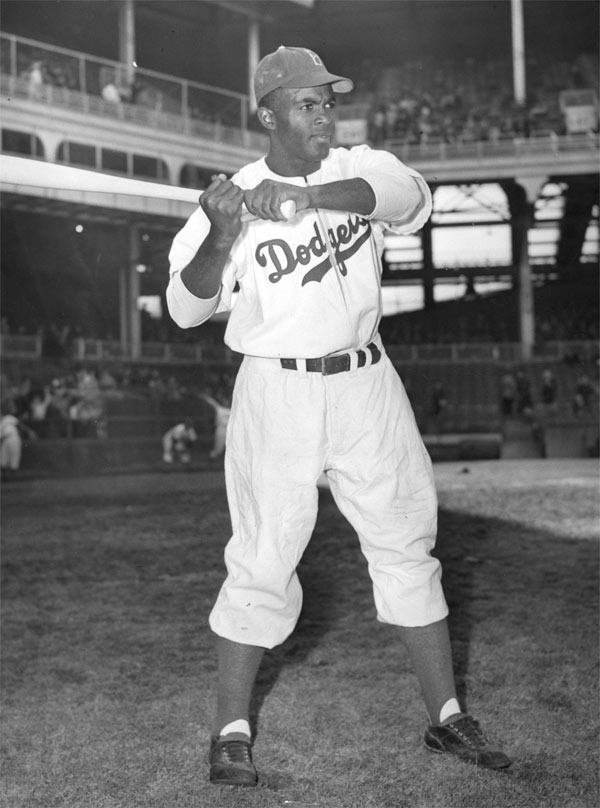

On April 11, Robinson tried on a Dodger uniform for the first time before an exhibition game against the Yankees. The uniform would not stay clean for long. (National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY)

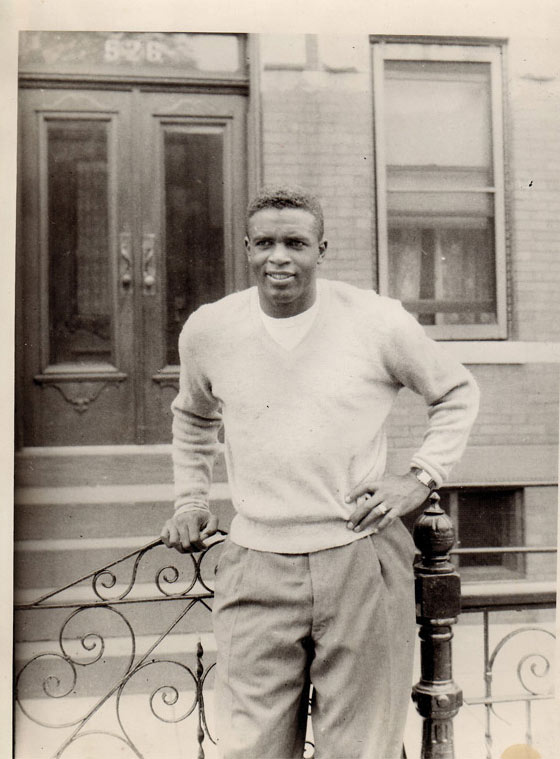

Early in the season, Robinson, his wife, and their five-month-old son moved into cramped quarters on MacDonough Avenue in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. The family rented one of two bedrooms in a two-bedroom, one-bath apartment, and remained there throughout the entire season. (Photo courtesy of Gilbert Jonas)

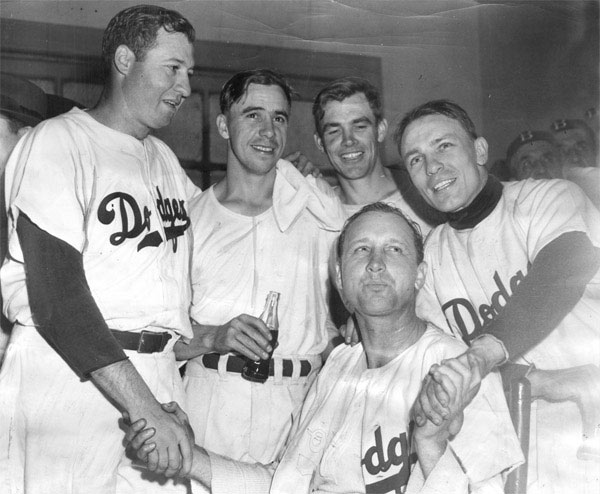

Heroes and Bums: Hugh Casey, Pee Wee Reese, Joe Hatten, Eddie Stanky, and (seated) Dixie Walker. (National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY)

The Yankees and Dodgers competed in one of the most exciting World Series competitions of all time, with Robinson leading the way. Here, Robinson is trapped in a rundown, but as he draws the attention of four Yankees, teammate Pete Reiser sneaks into second base. (National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY)

Robinson tries to break up a double play--and flattens Yankee shortstop Phil Rizzuto. Rizzuto would stay in the game. Later, Robinson would apologize for the hard hit. (National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY) |

||

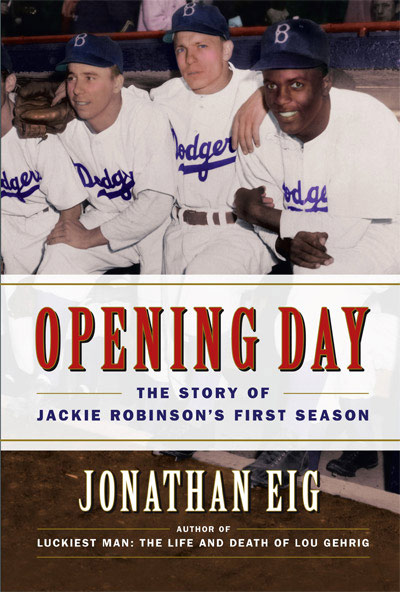

To buy the book, click the cover. |

© 2007 Jonathan Eig, all rights reserved.