Interview with Jonathan Eig Q: In your new book, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson's First Season , you write, that Jackie Robinson's “story has been told countless times – in poems, movies, songs, short stories, sermons, novels, comic books, term papers, plays and children's books.” So what made you want to write your own book about Robinson? A: Robinson's story was beginning to sound like folklore to me. It was becoming difficult to tell where the real man left off and the legend began. I wanted to separate the fact from the fiction. Did Robinson have flaws? Did he suffer doubts? I had no idea, and I was curious. Also, it occurred to me that the essence of his story could be captured entirely in the course of his rookie season. It was a glorious, frightening, thrilling season--and that was a story that had never been told. Q: Robinson had been a football star at UCLA and considered himself a mere dabbler in baseball. How did he get involved in the game that would make him a legend? A: The money drew him to baseball. Black athletes didn't have a lot of opportunities in the early 1940s, but Negro-League baseball was a thriving enterprise at the time, and teams offered good salaries for talented black baseball players. The Kansas City Monarchs offered Robinson $400 a month. Otherwise he probably would have wound up coaching basketball at an all-black high school or college. Q: What do you mean when you write that Robinson fit into the Negro Leagues “like a schoolmarm in a brothel”? A: If you cared about winning, you wanted a guy like Robinson on your team. If you cared about having a good time, you wanted nothing to do with him. The man was very tightly wound. He could be a real pill at times. His stern demeanor fueled his bid for greatness, but it did not make him a lot of fun to be around. I think it's safe to say that he and Satchel Paige were not running buddies. Q: You write that Robinson “was not the most talented black ballplayer in the country. He had a weak throwing arm and a creaky ankle. He was short on experience, and at twenty-eight, a little bit old for a first-year player.” So why was he selected to change history? A: Credit goes to Branch Rickey. Rickey spotted something in Robinson that no one else knew was there—save perhaps Robinson's wife, Rachel. Rickey believed that Robinson had the right combination of talent, intelligence and ferocity to get the job done. It may have been the single greatest piece of scouting in the history of professional sport. Q: What episodes during Robinson's stint in the military presaged the anti-segregation stance he would ultimately take on a national stage? A: In 1944, while serving on an Army base in Texas, Robinson was court-martialed for refusing an order from a white bus driver to move to the back of a bus. This was eleven years before Rosa Parks came along. Robinson not only stood up to the bus driver, he stood up to the U.S. military. It was an enormous risk. He could have wound up in jail, his future down the drain. But he took the stand at his trial and complained that he was being singled out because some white officers didn't like taking lip from an “uppity” black lieutenant. He was found not guilty of all charges. The episode revealed that Robinson wasn't afraid of questioning authority and wouldn't accept the status quo. Q: Why was New York, and specifically Brooklyn, the inevitable staging grounds for this great experiment? A: New York City after the war was an unbelievably exciting place. So much was changing. There was a sense that a new age was dawning, and many black men and women were determined to seize the moment and improve their fortunes. Long before anyone had ever heard of Martin Luther King Jr. or affirmative action, a powerful civil rights movement was emerging in New York City. And while the movement had its center in Harlem, Brooklyn was the best place to see its effects. In Brooklyn, you had every ethnic group and every social class. Yet for all the differences in the community, every man woman and child seemed to be united by two things: a desire to stake a claim to the American Dream, and a desperate yearning to see the Dodgers win a World Series. A lot of white men in Brooklyn viewed Robinson as a Dodger first and a black man second. I don't think he would have had the same kind of reception in Boston or St. Louis. Q: The other major player in the Jackie Robinson story is Dodgers owner Branch Rickey. What were Rickey's true motives? A: Baseballically speaking, to use my favorite Rickey phrase, his desire was to bring the championship flag to Brooklyn. Of course, Rickey was a complex man, and his motives were complex. He wanted to win. He also wanted to serve God. He wanted to move America away from its system of racial segregation. He wanted to make money. He wanted to sign the nation's best black players before other teams got them. And he wanted to cement his legacy as baseball's most brilliant executive. The amazing thing is that he accomplished every one of those goals. Q: The NFL signed its first black players at around the same time as Robinson was joining the Dodgers, so why was it the integration of baseball that became such a significant event in America? A: Baseball was far and away America's most popular game in 1947. No other sport held such a grip on the nation. What's more, it was a game played every day for eight months of the year. There were famous black athletes before Robinson--Joe Louis and Jesse Owens, to name two of them. But they competed as individuals. Robinson was part of a team. He had to do more than win—he had to fit in, too. That made him the perfect symbol of integration. Q: Many mainstream newspapers barely covered Jackie Robinson's opening day. Why the relative silence? A: Have you ever seen a ballplayer take his first turn at bat in the majors and just stand there, frozen, watching pitches go by? The writers covering the Dodgers on April 15, 1947, had never seen anything like this. They were trained to cover hits, errors and outs, not revolutions. They froze. Q: You write that it is often the case where Robinson's rookie year is concerned that fact and legend intertwine. How did you get to the truth when researching and writing Opening Day ? A: I took nothing for granted. I relied as much as possible on original and contemporaneous reporting. I interviewed all the ballplayers and all the eyewitnesses I could, but I always double-checked what they told me against newspaper accounts. A lot of these old ballplayers, God bless them, have been telling tales for so long that they're on auto-pilot when they give interviews. I pushed them hard for concrete details whenever possible. I also benefited enormously from my time with Rachel Robinson. Truth be told, I bugged the daylights out of her. But she's a great truth-teller. Almost everything she told me checked out. Q: Jackie Robinson's story is also the story of his wife, Rachel. Could he have done what he did without her by his side? A: It's difficult to imagine Jack succeeding without his wife. Rachel was so strong and so smart and so deeply in love with him. Their living arrangements were just awful. The Robinsons were a family of three—including a cranky baby—crammed into a 10-foot-by-12-foot room for an entire season. No friends. No family. If Rachel hadn't been such a rock, I shudder to think what might have happened. Jack was a very lucky guy, and he knew it. Q: A peripheral character in the story you tell is Malcolm X – not one we normally associate with baseball history. What was his relationship to Jackie Robinson? A: Malcolm X was still known as Malcolm Little in 1947. He was a 21-year-old inmate at Charlestown State Prison in Massachusetts, and he listened to every Dodger game on the radio that year, keeping score in pencil. He described himself as Robinson's biggest fan. At that moment, the notion of integration thrilled and inspired him. He determined at about this time to get his act together, to make something of himself. Later, of course, he would reject Robinson's approach and embrace a more militant view. In fact, he and Robinson would become staunch political enemies. But in '47, they were fighting for the same team. Q: Considering the risk he endured, was Robinson paid well for his efforts? A: No. He received the league's minimum salary of $5,000. Branch Rickey made almost all the right moves in 1947, but I think he blew this one. He should have paid Robinson at least twice that—not because Robinson endured abuse, but because he was a player of astounding ability, because he drew huge crowds everywhere he went, and because Rickey had asked Robinson to refrain from making endorsement deals for much of the season. Q: Robinson died relatively young, having lived a long time with poor health. Did his experiences during his ten years in the majors contribute to his early demise ? A: I suspect Robinson's approach to the game did shave some years from his life. He carried an enormous burden, and he did not carry it easily. Then again, his personality was such that he probably would have experienced stress in any line of work. He felt compelled to fight injustice wherever he found it—and he found it almost everywhere. We can all be grateful, but I think he paid a price.

|

||

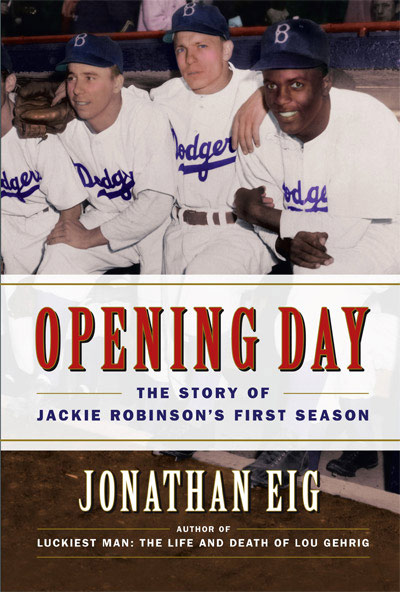

To buy the book, click the cover. |

||

April 15, 1947, marked the most important opening day in baseball history. When Jackie Robinson stepped onto the diamond that afternoon at Ebbets Field, he became the first black man to break into major-league baseball in the twentieth century. World War II had just ended. Democracy had triumphed. Now Americans were beginning to press for justice on the home front—and Robinson had a chance to lead the way. He was an unlikely hero. He had little experience in organized baseball. His swing was far from graceful. And he was assigned to play first base, a position he had never tried before that season. But the biggest concern was his temper. Robinson was an angry man who played an aggressive style of ball. In order to succeed he would have to control himself in the face of what promised to be a brutal assault by opponents of integration. In Opening Day, Jonathan Eig tells the true story behind the national pastime's most sacred myth. Along the way he offers new insights into events of sixty years ago and punctures some familiar legends. Was it true that the St. Louis Cardinals plotted to boycott their first home game against the Brooklyn Dodgers? Was Pee Wee Reese really Robinson's closest ally on the team? Was Dixie Walker his greatest foe? How did Robinson handle the extraordinary stress of being the only black man in baseball and still manage to perform so well on the field? Opening Day is also the story of a team of underdogs that came together against tremendous odds to capture the pennant. Facing the powerful New York Yankees, Robinson and the Dodgers battled to the seventh game in one the most thrilling World Series competitions of all time. Drawing on interviews with surviving players, sportswriters, and eyewitnesses, as well as newly discovered material from archives around the country, Jonathan Eig presents a fresh portrait of a ferocious competitor who embodied integration's promise and helped launch the modern civil-rights era. Full of new details and thrilling action, Opening Day brings to life baseball's ultimate story. |

© 2007 Jonathan Eig, all rights reserved.