|

I was born in New Jersey but my family moved south before I was old enough to remember anything, so I grew up a southerner, in Nashville, Tennessee. I left Nashville to go to college at Georgia Tech and remained in Georgia for the next ten years. When I graduated from Georgia Tech I worked for Lockheed Aircraft Company, which in 1966 sent me to England for a year to work as a design engineer on the C-5A cargo plane. I was born in New Jersey but my family moved south before I was old enough to remember anything, so I grew up a southerner, in Nashville, Tennessee. I left Nashville to go to college at Georgia Tech and remained in Georgia for the next ten years. When I graduated from Georgia Tech I worked for Lockheed Aircraft Company, which in 1966 sent me to England for a year to work as a design engineer on the C-5A cargo plane.

My time in England coincided with the escalation of the Vietnam War. Opposition to that war would become a central passion of my life for the next several years. When I returned from England to Georgia, I resigned from Lockheed in a public act of protest against its role as a war profiteer. As a result, I became virtually unemployable for a while as the FBI dogged my trail, warning prospective employers against hiring me. (I suspected this at the time and confirmed it years later when I got my FBI files via a Freedom Of Information Act request.)

But through my antiwar activity I became acquainted with the Rev. Andrew Young, one of Dr. Martin Luther King's main associates in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Rev. Young's wife, Jean Young, was not intimidated by the FBI, so she hired me into a work-study program called the Teacher Corps. That resulted in a job as a teacher in the Atlanta Public Schools and a masters degree in education from the University of Georgia.

I had married earlier, while I was still a student at Georgia Tech, and by 1968 had three children, all daughters. But the marriage ended in about 1970, whereupon I moved to Manhattan with two of my daughters. I soon lost my southern accent and have been a New Yorker ever since. In 1980 the best thing that ever happened to me happened to me: I met my soulmate, Marush. I moved into her Upper West Side apartment and we married in 1982 and have lived “happily ever after.” Meanwhile, the daughters have produced a total of six grandchildren.

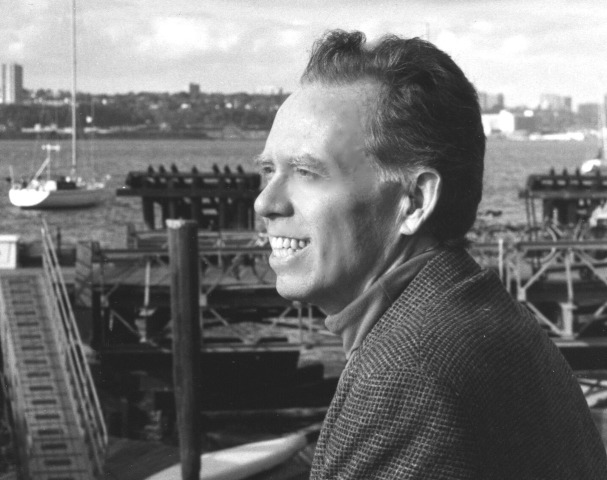

Cliff with Marush at sea

I've had a varied work history. A well-known book by Studs Terkel, Working, consisted of interviews with people with many different kinds of jobs who were asked, “What's it like to work on an automobile assembly line?” or “What's it like to be a coalminer?” I recall thinking that he could have produced a pretty big book just by interviewing me about all the different jobs I've had. Here's a list of the ones I can remember:

- construction worker

- autoworker

- printshop worker

- door-to-door bible salesman in rural Tennessee

- aircraft assembly-line worker and welder

- human factors engineer for Lockheed Aircraft Corporation

- New York City subway electrician

- preschool and kindergarten teacher

- education director of a Head Start center in the South Bronx

- history professor

- magazine editor

- freelance writer

- copyeditor for one of the (then) Big Six accounting firms

- financial proofreader

Career stability was not my strong suit. Along the way, I was a member of at least five different unions: The International Association of Machinists, the United Auto Workers, the Transit Workers Union, the American Federation of Teachers, and the Professional Staff Congress. And as the song says, “I’m sticking with the union.” Although I haven’t seen an auto assembly line for years, I find myself once again belonging to the United Auto Workers. That’s because I’m currently a paid-up member of the National Writers Union, which happens to be UAW local 1981/AFL-CIO.

I was out of work and on the dole for a few months in the mid-seventies when a friend of mine suggested that I become a proofreader. I said, “You mean I can make good money based on nothing more than the ability to read the English language?” My friend not only assured me it was true, but he filched the proofreading test from the place he worked and coached me on it, so of course I got the job. Fortunately for all concerned, I proved to be good at it.

It was at an ad shop named Cardinal Type, which no longer exists. It soon dawned on me that there were different kinds of proofreaders, and some were making much more money than others. The lowest paid, I think, worked for publishing houses; then there were the legal proofreaders, and then the ad-shop proofreaders. But the best-paid of all—back then, at least—were the financial proofreaders. When the mammoth corporations do their multibillion-dollar deals, some of the crumbs off their table fall to the financial printers, and some of those crumbs can be quite substantial. So I thought, “Show me the money!” and became a financial proofreader.

But it was just a job—I didn't consider “proofreader” to be my essential identity. When I was in my mid-forties, one of my daughters said to me, “Dad, I don't know what I want to do with my life.” I replied, “Welcome to the club. I don't know what I want to do with my life either!” But I did eventually settle down to choose a career path—better late than never. In 1985 I decided I wanted to be a historian, so I went back to school and got the requisite Ph.D. degree.

I attended classes at night and was able to do a hundred percent of the coursework for the Ph.D. during the day, on company time at my proofreading job. I didn't have to cheat the company to do it; the nature of financial proofreading was such that about ninety percent of the workday was “downtime”: waiting for work. If that seems massively inefficient, it was, but that was how the financial printing industry was structured. The work was determined by the presence or absence of the client corporations' lawyers who produced the written material that we were to proofread. Those clients were financial giants with unlimited resources—money to burn, so to speak—so it didn't matter to them if they were paying idle proofreaders to sit around and wait until they had something for us to read. All they demanded was that when they wanted service, they wanted it immediately.

The one thing I couldn't do on the job was dissertation research. Fortunately, I got laid off at an opportune moment and was able to collect unemployment benefits during the period when I was writing my dissertation. My topic was science during the French Revolution, which gave Marush and me a good reason to spend some time in Paris.

After getting the Ph.D. degree, I found that the job market for historians in their fifties was rather thin—in fact, virtually nonexistent. For a few years I scratched out a living as an adjunct professor of history. I loved teaching, but was disgusted with the level of exploitation that adjuncts have to suffer, so I returned to financial proofreading. My reeducation as a historian was not wasted, however. On January 1, 2000—the dawn of the new millennium—I resigned from my proofreading job and commenced life as a full-time author of books on historical subjects.

|

|

Photo of Cliff Conner by Harry Glaser Photo of Cliff Conner by Harry Glaser

|

|