Crash

IV

Mazzocchi had prepared himself for the worst imaginable outcome at the Cimarron plant. “I had promised her a job in New York, at Group Health Insurance,” he said, “and I had that nailed down for her. I thought she was going to get fired. Who thought she was going to get killed?” Mazzocchi had prepared himself for the worst imaginable outcome at the Cimarron plant. “I had promised her a job in New York, at Group Health Insurance,” he said, “and I had that nailed down for her. I thought she was going to get fired. Who thought she was going to get killed?”

After receiving the news, Wodka, Burnham, and Stephens rushed to the crash scene in search of evidence. The car had already been towed, but they snooped around looking for tracks and skid marks, finding nothing except some detritus from the crash.

They scrambled to locate Karen's car and to get a report from the Oklahoma Highway Patrol. Trooper Rick Fagen, who investigated the accident, told them that he believed Silkwood fell asleep at the wheel. Her car had crashed into a concrete culvert, and Karen had been impaled by her steering wheel. When Wodka suggested the possibility of foul play, Fagen forcefully dismissed the notion.

Wodka and Drew Stephens convinced Silkwood's parents to allow the authorities to release the vehicle to Stephens so that it could be further examined.

The next day, Fagen interviewed workers at the plant, especially those who saw Karen at the union meeting. He also examined evidence from the car, finding what he believed were two marijuana joints and some sedatives. His report insinuated that Silkwood crashed after passing out while under the influence of drugs.

Fagen reported that he found no documents in Silkwood's car.

Mazzocchi seriously considered the idea that Silkwood's death may have been purely accidental. Yes, her death did represent a stroke of good luck for the company she had been targeting, but it was entirely possible that while traveling down that dark road, Silkwood ran into the culvert by accident . Burnham suggested the union hire a crash investigator, and Wodka convinced Mazzocchi to do it.

Wodka located A. O. Pipkin, a former cop who had investigated more than two thousand cases and testified in over three hundred trials. Pipkin, who demanded no interference from the union, meticulously examined the car and the scene of the accident. He would later bring in another expert to go over his findings as well. What Pipkin initially reported to the union directly challenged the Oklahoma Highway Patrol report.

Pipkin said Silkwood hadn't fallen asleep or passed out at the wheel: The steering wheel was bent back on the sides, proving she'd been wide awake and hanging on tight as she tried to maintain control.

Pipkin also questioned how it was possible for someone who was asleep or in a drugged stupor to leave the road at a forty-five-degree angle and then drive along the grassy shoulder in a straight line until flying over the culvert and crashing into the wing wall.

What's more, Pipkin's microscopic analysis of a dent in Silkwood's back bumper showed that it was new and could not have been caused by either the crash or the towing of the wreck. Silkwood's death, he concluded, was no accident.

“It is my opinion,” wrote Pipkin in his report, “there is enough circumstantial evidence present to indicate that V-1 [Silkwood's vehicle] was struck from the rear by an unknown vehicle, causing it go out of control, due to either the initial impact or to the combined impact and driver over-reaction.”

He put it more bluntly to Burnham and The New York Times on November 19: “I am not accusing any particular person of murder. Based on an independent investigation, however, it is apparent that someone forced Karen Silkwood from the road, therefore causing her death. I'll leave it to the Federal authorities to determine who and why.”

Did Mazzocchi and Wodka have a murder on their hands? Perhaps. Over and over, they tried to fit the facts into a more benign framework. Maybe someone from the company, or associated with it, wanted to scare Karen and bumped her car to get her to pull over and give back the documents, not realizing that the culvert was up ahead. Almost thirty years later, both Mazzocchi and Wodka still viewed it that way:

Wodka: Looking back, people did know what she was up to . . .The word did get out. And somebody put two and two together and realized that that night she was going to meet with the reporter—and was, I think, just trying to get whatever papers she had—not to kill her, or drive her off the road—but, basically . . .

Mazzocchi: . . . Scare her. You know, in retrospect, you get involved in these things. You don't think somebody's gonna murder somebody. And I'm sure they didn't set out to murder her. Whoever drove her off the road that night set out to scare her. I mean, the chance of her hitting this cement culvert was remote. I mean, how many are there out in the field? . . . I don't think somebody went out to kill her that night—'cause on that road, to try to kill somebody, was serendipity. I mean, I think the guy was bumping her car—I think we have good evidence of that. And that culvert was there. And the car hit it—and, you know, it leaped over this thing, and she got impaled on the steering wheel . . .

Wodka: I mean, she's driving a Honda Civic . . . They were tiny, tiny cars . . . And I've driven up and down that road. It's a dark, two-lane highway. I mean, you go for miles and miles. There's nothing but farms and fields . . . So it was a good place to do it.

I remember asking her—she had been contaminated; she had lost all her possessions; she had lost her home. And she had gone out to Los Alamos. She had gone through the whole body counter . . . She had come up with a count—the whole thing. I remember talking to her. I said, “Do you still want to go ahead, or not?” — Like “I got to chill out for a while” or “I gotta get my life back together.” She said, “No, I want to go ahead.” So we went ahead.

Were Kerr-McGee employees directly or indirectly involved? Mazzocchi thought the company's behavior after the crash was suspicious. For one thing, when Kerr-McGee heard that the union had hired Pipkin, it promptly hired the notoriously anti-union Pinkerton Detective Agency to investigate not Pipkin's findings, but Pipkin himself. When OCAW released Pipkin's results, Kerr-McGee leaked stories about alleged problems with Pipkin's credentials, suggesting he was a shady operator. None of these allegations turned out to be true.

Then Kerr-McGee flexed its raw corporate power to crush the controversy. From depositions, Mazzocchi later learned that Kerr-McGee was briefed regularly by the state police and the FBI about the Silkwood investigation—just as it had been informed in advance of “surprise” health and safety inspections. As Wodka noted, “Kerr-McGee had so much control and influence with the Atomic Energy Commission, they didn't need to influence any investigation through the media. ”

To Wodka, the most terrifying thing was the lie detector test Kerr-McGee required workers to take when the company interrogated them about Silkwood. “They just forced the workers to take it. If they refused, they could be fired. If they took the test and it showed inconsistencies, they could be fired. If they told the truth about how they were helping the union, they could be fired as well.”

The questions Kerr-McGee asked workers were outrageous: According to union affidavits and filings with the National Labor Relations Board and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, on December 23, 1974, Kerr-McGee asked the following :

Did you know or ever talk to Steve Wodka?

Do you belong to the union?

Did you know or ever speak with Karen Silkwood?

Have you recently seen or talked to Drew Stephens [Silkwood's boyfriend] ?

Did you ever do anything detrimental to Kerr-McGee?

Did you ever have an affair with a fellow employee?

Did you ever talk to the press?

Although the union urged its members not to participate, many who feared for their jobs succumbed.

Union officer Jerry Brewer was fired for an unproven time-card irregularity, going to his car during break time, and “his attitude.” Shop chair Jack Tice was transferred to a remote area of the facility, and a manager was assigned to watch him constantly, even following him to the bathroom.

And in case any of the farm boys were still too thick to get the antiunion message, Kerr-McGee abruptly shut the facility down (with no pay) for two weeks during the holiday season.

As Mazzocchi said on ABC's Reasoner Report, “Workers have been fired, fingerprinted, and given lie detector tests. The plutonium police state has arrived.”

Mazzocchi and Wodka used every tool at their disposal to keep the heat on Kerr-McGee. They pressured the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to rule on the union's health and safety complaints. They asked the National Labor Relations Board to reinstate Brewer and Tice. They urged the FBI to investigate of the crash. They called for a congressional investigation. And Mazzocchi worked the media hard.

David Burnham wrote seven stories over the next month in The New York Times, giving the union ample opportunity to air its case. On November 19, Burnham revealed Pipkin's initial findings in a story headlined, “Death of Plutonium Worker Questioned by Union Officials.” The next day, in an article titled “Plutonium Plant Under Scrutiny,” Burnham reported that the AEC would investigate allegations that “an Oklahoma plutonium factory had been falsifying the inspection records of fuel rods to be used in an experimental reactor.”

A controversy erupted over whether or not Karen was asleep at the wheel. The Oklahoma police had said Silkwood was exhausted from her long drive back from Los Alamos the night before her crash. Burnham reported she actually had flown back a day earlier. The Oklahoma medical examiner said that Silkwood was under the influence of “a sedativehypnotic drug, methaqualone, associated with traces of ethyl alcohol.” But ABC's Reasoner Report, using Pipkin's findings, forced the Oklahoma State Police chief to admit on the air that Silkwood had been wide awake at the time of the crash, because the steering wheel was pushed back on its sides.

There was also a controversy about how the plutonium got into Silkwood's house and into her body. Rumors circulated that she smuggled plutonium out of the factory in her vagina, and then poisoned herself to embarrass the company and help the union. Others alleged she was part of a plutonium smuggling ring. In early January, the AEC released a report revealing that Silkwood did not have ready access to the specific type of plutonium found in her in body (AEC isotope studies can detect differences in each lot of plutonium pellets). The AEC also concluded that someone had spiked two of her urine sample with plutonium. The report could not explain how the plutonium got into her house and food. In “AEC Can't Say How Worker Swallowed Plutonium,” Burnham wrote that AEC officials had told Wodka there was “absolutely no evidence to suggest that Miss Silkwood had been smuggling plutonium.” No smuggling evidence against her ever surfaced.

The blame-the-victim corporate offensive continued. In December, three plutonium accidents occurred at the Cimarron plant in one day, prompting the AEC to investigate. Kerr-McGee told the Times it had “evidence that some of the incidents have been contrived.” No evidence was forthcoming.

But Tony and the press couldn't find the original smoking gun: The papers and photographs Silkwood had planned to deliver documenting the faulty control rods had vanished.

A backlash started to build. When National Public Radio's Barbara Newman and Peter Stockton visited the Cimarron area, they found a great deal of hostility toward Silkwood: More than a few referred to her as “that bitch” who had threatened their jobs. Even Tice and Brewer had become critical of the union after learning that Silkwood had done undercover work without their knowledge.

Mazzocchi also could feel the pendulum inside the union swinging not only against Silkwood, but against him as well. OCAW officials wanted him to back off. The union had already paid for Pipkin and for the hundreds of hours that Wodka and Mazzocchi had spent pressing public agencies and the media to investigate. The Kerr-McGee workers were becoming increasingly hostile, and some unionists worried that the Silkwood publicity was harming the interests of all atomic workers .

OCAW vice president Swisher arranged a quiet meeting between the union's top officers and Dean McGee to patch things up. As Mazzocchi recalled :

I got called to Denver to meet with McGee himself. Because Swisher got to Grospiron, who says: “You know, this publicity is bad stuff for us.” So when I got in the room with Dean McGee, I said, “First of all, you tried to decert the union.” He denied that. I took a fuckin' leaflet out that the company had put out. He said, “Well, I didn't know anything about that.” I said, “Well . . . the place is a bloody mess. You did nothing to clean it up.” He said, “Well, wewant to cooperate—we want to turn over a new leaf.”

I said, “Fine. But we're not gonna lay off following up on who killed KarenSilkwood.”

Grospiron said, “Yeah, we're not.” The company just wanted to get us off the Silkwood thing. So McGee left, and I left, and we continued to do what we did. I give Grospiron credit. There was a lot of pressure on him.

Grospiron's resolve had limits. Union officers soon ganged up on Mazzocchi and told him to stay away from the press. But Mazzocchi worked incessantly behind the scenes, talking about Silkwood to reporters, to movement activists, to anyone who would listen. The murkiness of the Silkwood case invited innuendo, hearsay, and paranoia; Mazzocchi was determined to stick to facts and plausible theories. It felt to Tony as if “nobody knew about what happened to Karen—nobody cared. She was dead. I tried to get people interested in it, and I couldn't.”

With Burnham running out of leads and top OCAW officers growing impatient, Mazzocchi was left virtually alone in his dogged quest for the truth about Karen Silkwood. He never considered that Silkwood's killers might come after him.

Then, on, the night of January 17, 1975, Mazzocchi blacked out while driving home from an AFL-CIO health and safety conference in Warrenton, Virginia. His car hit the grass median, flipped into the air, and landed upside down. Its roof was smashed to the steering wheel .

Miraculously, Mazzocchi survived.

The accident, coming just two months after Silkwood's, alarmed the famously unflappable, practical-minded union leader. Mazzocchi couldn't help thinking about how much the nuclear industry would have benefited from his death. “If they knocked me out, the union would have shut up about Silkwood,” Mazzocchi said. “There was a lot of pressure in the union to get off it. If I had died, it would have been over with. There wouldn't have been a story.”

After his crash, Mazzocchi redoubled his efforts. He convinced Ronnie Eldridge, the editor of Ms. Magazine, to cover the story. Eldridge assigned B. J. Phillips, who wrote “The Case of Karen Silkwood” for the magazine in the spring of 1975. Mazzocchi also worked with Howard Kohn at Rolling Stone, who in March wrote a more provocative piece titled “The Nuclear Industry's Terrible Power and How It Silenced Karen Silkwood.” Barbara Newman did a March segment for National Public Radio, updating her December report.

The Ms. connection ignited two feminist organizers, Kitty Tucker and Sarah Nelson, from the National Organization for Women (NOW), to pick up the Silkwood story. “It would be terrific if the women's movement does something about this,” Mazzocchi told them.

Tucker and Nelson set up Supporters of Silkwood (SOS). They made November 13, 1975, Karen Silkwood Memorial Day, and put her front and center in NOW's “Stop Violence Against Women” campaign. They mobilized local chapters to write to their senators asking for a congressional investigation. They circulated petitions. They notified the local press and held rallies and candlelight parades in several cities to the cry of “Who Killed Karen Silkwood?” Their superb organizing, coupled with increasing interest in the women's movement, drew the media.

When NOW leaders visited the Justice Department in August 1975 to demand a thorough investigation of Silkwood's death, according to one account “nearly 100 reporters and TV crew members were waiting in the corridor and on the stone steps.”

The activists shepherded Silkwood's cause through congressional hearings and into a 1979 civil trial pleaded by Danny Sheehan, an idealistic young lawyer, and the more seasoned and famed attorney Gerry Spense. After the longest civil trial in Oklahoma history, the jury awarded Karen's father and children a $10.5 million verdict against Kerr-McGee.*

*Kerr-McGee appealed, and in 1985 the Tenth Circuit Court ordered a new trial. Kerr-McGee then offered the family $1.38 million; the case was settled out of court . Soon Hollywood producers and others were vying for the movie rights. As Mazzocchi recalled :

Gloria Steinem popped into my office with B. J. Phillips, and they wanted exclusive rights to the Silkwood stuff. I said, “I'm not going to give you exclusive rights. This story belongs to everybody. If anybody wants to make a movie of it, they should.”

They start jumping up and down. B. J. Phillips said that she wrote the first article. So I said, “Yeah. So? It was a lousy article to start with. Hey. Just because you wrote one story, it doesn't give you exclusive rights.” So they stormed out of the office .

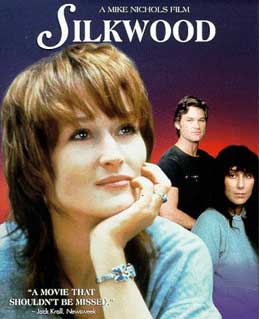

Soon after, Mike Nichols directed the movie Silkwood, starring Meryl Streep as Silkwood; Cher as Silkwood's roommate Sherri Ellis; Kurt Russell as her boyfriend Drew Stephens; and Ron Silver as Steve Wodka .

“Mr. Nobody played Mazzocchi,” said Wodka with a chuckle.

“It was ABC, of all people, that did Silkwood, Tony said. “We told them we wouldn't give them any information unless they named Kerr-McGee and the union. And they did it. Cher said that Streep asking her to play the role of Sherri resurrected her career.”

We gave Streep the tapes of the union's conversations with Silkwood, because we had taped Karen every time she called us. And we described Karen to Streep. And then, when I looked at the movie, Streep had all Karen's body motions. And for you to describe another human being, and how they move, and then see the actor move in exactly the same way—it was incredible .

And yet physically, Mazzocchi said, “It was Cher who was the dead ringer for Karen. ”

By 1983, when the movie was released, thousands of activists had already turned Karen Silkwood into a genuine American heroine. Mazzocchi was thrilled by these events, but he also wanted to set the record straight. As he told the OCAW convention in 1979:

I have nothing against feminism, but Karen wasn't a feminist. She's been adopted by the feminist movement . . . She has been portrayed as an anti-nuclear activist. She wasn't. She was involved in one simple activity; it was to save a local union at Kerr-McGee where the company was hell bent on destroying it . . . Karen was solely a trade union martyr . . . She made the supreme sacrifice.

Next | Page 2 3 4 5 |